The Central American Isthmus: Land Bridge of the Americas

The Central American Isthmus, a land bridge linking North and South America, transformed global systems 3 million years ago through the Great American Biotic Interchange. It hosts 7% of Earth's biodiversity in less than 1% of land and serves as a key gateway for global commerce via the Panama Canal.

Central America: The Strategic Land Bridge of the Americas

The Central American Isthmus stands as one of Earth's most remarkable geographic features—a narrow strip of land that fundamentally altered the planet's biological, oceanographic, and climatic systems. Stretching approximately 2,000 kilometers (1,243 miles) from southeastern Mexico to northwestern Colombia, this vital land bridge connects North and South America while separating the Pacific Ocean from the Caribbean Sea.

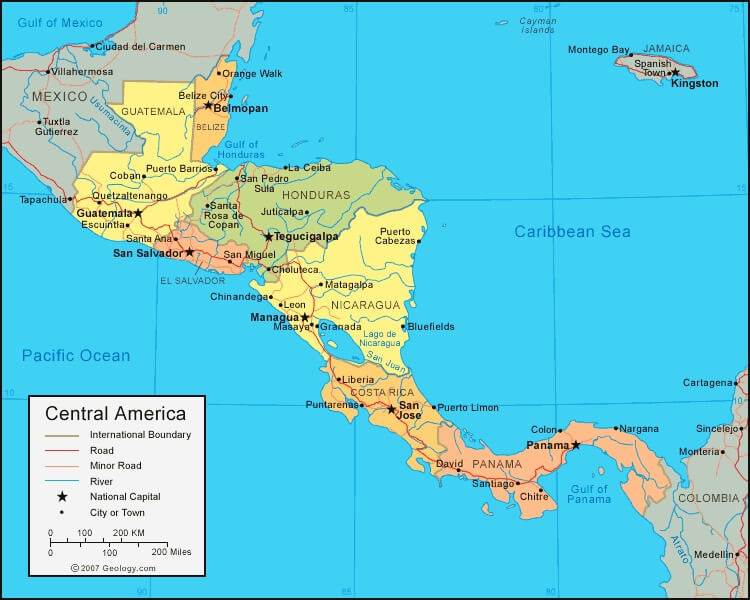

Covering approximately 518,000 square kilometers (200,000 square miles), the isthmus encompasses seven nations: Belize, Guatemala, Honduras, El Salvador, Nicaragua, Costa Rica, and Panama. Despite occupying less than 1% of the world's land surface, this region harbors 7% of the planet's biodiversity. It serves as a critical corridor for global commerce, hosting the Panama Canal, which handles 6% of global trade annually.

The isthmus's emergence approximately 3 million years ago triggered one of the most significant evolutionary events in Earth's history—the Great American Biotic Interchange—fundamentally altering biological communities across two continents while reshaping global ocean circulation patterns and climate systems.

Relief map of Central America.

Physical Geography and Geological Foundation

Tectonic Setting and Mountain Formation

The Central American Isthmus owes its existence to complex interactions among three major tectonic plates: the North American, Caribbean, and Cocos plates. The Cocos Plate subducts beneath the Caribbean Plate at the Middle America Trench, creating the volcanic arc that forms the region's mountainous backbone and generating the magma that feeds numerous active volcanoes.

The continuous mountain chain extends from Mexico's Sierra Madre through Guatemala's highlands to Costa Rica's Cordillera de Talamanca, reaching maximum elevation at Volcán Tajumulco in Guatemala at 4,220 meters (13,845 feet). This topographic complexity creates the fundamental framework that influences regional climate, hydrology, and biogeography.

Volcanic activity remains a defining characteristic, with over 60 historically active volcanoes forming part of the Pacific Ring of Fire. Notable active systems include Arenal in Costa Rica, Masaya in Nicaragua, and Volcán de Fuego in Guatemala. While creating significant hazards, these volcanoes generate the region's most fertile soils and contribute to extraordinary biological diversity.

The Great American Biotic Interchange

The isthmus's formation 3.1 million years ago represents one of geology's most significant recent events. Prior to closure, North and South America were separate continents, with continuous oceanic circulation between the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans.

The closing of the Central American Seaway fundamentally altered global ocean circulation, intensifying the Gulf Stream system and contributing to Northern Hemisphere glaciation cycles. Biologically, it enabled massive species migration between continents—the Great American Biotic Interchange.

North American species, including ancestors of modern jaguars (Panthera onca), horses, and camels, colonized South America, while South American species such as ground sloths, armadillos, and opossums moved northward. This interchange profoundly altered both continents' fauna and demonstrates how small geographic changes can trigger planetary-scale biological transformations.

Climate Systems and Biodiversity

Climate Zones and Weather Patterns

Central America's position between two oceans and dramatic topographic relief creates remarkable climatic diversity within tropical latitudes. Caribbean coastal lowlands experience tropical wet climates with annual precipitation of 2,000-4,000 millimeters (79-157 inches), while Pacific coastal regions exhibit tropical dry patterns with distinct wet and dry seasons and annual rainfall of only 1,200-1,800 millimeters (47-71 inches).

Highland areas above 1,500 meters (4,921 feet) maintain temperate conditions, with year-round temperatures of 15-20°C (59-68°F), creating climate zones that support temperate forest species within tropical latitudes.

The region experiences significant hurricane vulnerability along Caribbean coasts, with major storms like Hurricane Mitch in 1998 demonstrating extreme weather impacts that can cause thousands of fatalities and economic losses exceeding 50% of national GDP.

Extraordinary Biodiversity

Central America represents one of the world's most important biodiversity hotspots, containing approximately 20,000 plant species (30% endemic) and over 1,500 vertebrate species. This extraordinary diversity results from the region's position at the interface of two continental biological realms, dramatic elevation gradients that create numerous isolated habitats, and tropical conditions that are optimal for speciation.

Forest ecosystems range from lowland rainforests on Caribbean slopes to cloud forests at middle elevations and pine-oak forests in highlands. Caribbean lowland forests support large mammals, including jaguars and Baird's tapirs (Tapirus bairdii), while cloud forests provide habitat for endemic species like the resplendent quetzal (Pharomachrus mocinno), Guatemala's national bird.

Marine ecosystems on both coasts support distinct biological communities. Caribbean coral reefs form part of the Mesoamerican Barrier Reef System, the world's second-largest reef system, providing habitat for threatened species, including hawksbill (Eretmochelys imbricata) and leatherback (Dermochelys coriacea) sea turtles. Pacific waters experience seasonal upwelling that supports important commercial fisheries.

Endemic species exhibit high evolutionary uniqueness, with many found nowhere else on Earth. Examples include numerous endemic reptiles, amphibians, and plants that evolved in isolated mountain ranges and islands throughout the region.

The Panama Canal: Engineering Marvel and Global Gateway

Construction and Engineering Achievement

The Panama Canal represents one of humanity's greatest engineering accomplishments and the most significant geographic modification ever undertaken. French construction attempts beginning in 1881 failed catastrophically due to tropical diseases and engineering challenges, resulting in an estimated 22,000 deaths.

American construction from 1904 to 1914 succeeded through revolutionary disease control measures and innovative lock-based design. The project required excavating 268 million cubic meters (350 million cubic yards) of material and constructing massive concrete locks 33.5 meters (110 feet) wide. Over 5,600 workers died during construction, primarily from industrial accidents, despite improved tropical medicine.

Economic Impact and Global Significance

The Panama Canal's economic importance extends globally, with approximately 6% of world trade passing through its locks each year. The canal reduces shipping distances by up to 12,000 kilometers (7,456 miles) between Atlantic and Pacific ports, generating cost savings of $50,000-200,000 per transit.

Annual traffic includes 12,000-14,000 vessel transits carrying over 300 million tons of cargo, though recent drought conditions have significantly reduced operations. Despite challenges, the Panama Canal Authority generated $3.45 billion in revenue during fiscal year 2024, providing approximately 20% of Panama's national government budget.

The 2016 expansion added larger locks capable of handling "New Panamax" vessels, more than doubling cargo capacity through a $5.4 billion investment. However, the canal faces ongoing challenges from climate change, particularly drought, which reduces water levels in Gatun Lake, its primary water source.

Environmental and Social Impacts

Canal construction created ecosystem fragmentation, severing biological connections between North and South American populations of large mammals such as jaguars and tapirs. The canal corridor acts as a biogeographic barrier preventing gene flow between populations separated by only 80 kilometers (50 miles).

However, watershed conservation efforts have created positive outcomes. The Panama Canal Authority manages 155,000 hectares (383,013 acres) of protected forests that maintain water quality while providing habitat for endangered species, creating one of Central America's largest continuous forest blocks.

Political map of Central America.

Cultural Landscapes and Human Geography

Indigenous Heritage and Colonial Legacy

The isthmus has been continuously inhabited for over 12,000 years, with Indigenous peoples representing 5-10% of Central America's 50 million inhabitants today. The Maya peoples, the largest Indigenous group with approximately 6 million individuals, maintain 29 distinct languages and continue traditional agricultural practices, including milpa (forest garden) systems that preserve both crop diversity and forest ecosystems.

Spanish colonization, beginning in the 16th century, fundamentally altered settlement patterns, creating colonial cities with standardized planning and hacienda agricultural systems that concentrated land ownership. These colonial patterns persist today, with 2-3% of landowners controlling 60-70% of agricultural land in most countries.

Religious syncretism throughout the region reflects complex interactions between Spanish Catholic traditions and Indigenous spiritual practices, creating distinctive regional expressions that combine Catholic, Indigenous, and African elements.

Contemporary Economic Geography

Agricultural systems remain central to regional economies, with coffee, bananas, and cattle ranching occupying large areas of productive land. Coffee production generates over $3 billion annually and employs approximately 2 million people, though climate change threatens production by pushing optimal growing zones to higher elevations.

Manufacturing industries, particularly in El Salvador, Honduras, and Guatemala, employ over 500,000 people producing textiles and electronics for North American markets under preferential trade agreements.

Tourism capitalizes on extraordinary natural and cultural heritage, generating over $8 billion annually. Costa Rica leads ecotourism development, demonstrating how countries can build economies based on biodiversity conservation rather than resource extraction.

Environmental Challenges and Conservation

Deforestation and Habitat Loss

Central America has lost over half its original forest cover, with current deforestation rates of 2-3% annually in some countries. Cattle ranching accounts for 60-70% of forest loss, creating extensive but economically inefficient pastures. Agricultural expansion for palm oil and other export crops has accelerated deforestation along Caribbean coastal plains.

However, reforestation success stories demonstrate possibilities for forest recovery. Costa Rica increased forest cover from 24% in 1985 to 54% today through payments for ecosystem services, protected area expansion, and natural regeneration programs.

Climate Change Vulnerability

Central America ranks among the world's most climate-vulnerable regions due to geographic exposure to extreme weather, dependence on climate-sensitive agriculture, and limited adaptive capacity. The region has experienced 0.5-1.0°C (0.9-1.8°F) temperature increases over 50 years, with mountain areas warming most rapidly.

Precipitation changes include reduced dry-season rainfall and more intense wet-season storms. Sea level rise of 3-4 millimeters (0.12-0.16 inches) annually threatens coastal communities and ecosystems, while hurricane intensification increases the frequency of Category 4 and 5 storms.

Conservation Success Stories

The Mesoamerican Biological Corridor represents one of the world's most ambitious conservation initiatives, connecting protected areas from Mexico to Panama through over 100,000 square kilometers (38,610 square miles) of core areas, buffer zones, and biological corridors.

Payment for ecosystem services programs provide economic incentives for forest conservation while supporting rural livelihoods. Community-based conservation has achieved notable successes, with Indigenous territories showing significantly lower deforestation rates than surrounding areas.

Species recovery programs demonstrate conservation effectiveness. Costa Rica's scarlet macaw (Ara macao) population increased from fewer than 20 breeding pairs in the 1990s to over 800 individuals today, thanks to dedicated conservation efforts.

Regional Integration and Future Prospects

Transportation and Economic Integration

The Pan-American Highway provides the only continuous overland connection between North and South America, extending 3,400 kilometers (2,112 miles) through the region. Major ports on both coasts handle millions of tons of cargo annually, serving as critical links between regional economies and global markets.

Economic integration through the Central American Common Market has eliminated most intraregional tariffs, creating over $6 billion in annual regional trade. The Dominican Republic-Central America Free Trade Agreement (CAFTA-DR) generates over $30 billion in annual trade with the United States.

Remittance flows from Central Americans abroad exceed $20 billion annually, providing crucial foreign exchange that supports family welfare and local economic development.

Conservation Leadership and Sustainable Development

Central America has emerged as a global leader in innovative conservation approaches integrating biodiversity protection with sustainable development. Ecotourism development has created economic alternatives to environmentally destructive activities, generating revenues to support conservation efforts.

Regional cooperation on transboundary conservation has developed effective management approaches for shared ecosystems and migratory species, including initiatives such as the Trinational Corridor, which protects critical jaguar habitat across Guatemala, Belize, and Mexico.

Conclusion

The Central American Isthmus demonstrates how relatively small geographic features can create profound global impacts extending far beyond their physical boundaries. From triggering the Great American Biotic Interchange 3 million years ago to serving as a critical corridor for modern global commerce, this narrow land bridge has fundamentally shaped planetary biological, oceanographic, and economic systems.

Today, the region exemplifies both opportunities and challenges facing developing areas in the 21st century. Countries throughout Central America have demonstrated remarkable innovation in conservation and sustainable development, providing models for other regions. However, unprecedented challenges from climate change, environmental degradation, and social inequality threaten both human welfare and ecological integrity.

The isthmus's extraordinary biodiversity, concentrated in less than 1% of global land area, provides essential ecosystem services, including climate regulation and genetic resources that benefit the entire planet. Its success in balancing development needs with environmental protection will influence global approaches to sustainable development in an era of increasing environmental constraints.

As the world faces mounting challenges from climate change and biodiversity loss, the Central American Isthmus provides both a window into these global challenges and examples of innovative solutions. The region's future will depend on maintaining a balance between development and conservation while adapting to changing international conditions that call for new approaches to sustainable development in one of the world's most important bridge regions.

Map depicting the seven countries of Central America and their capitals.